Financial Times: Macau casino operators fear end of winning streak

- Alidad Tash

- Sep 22, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Nov 3, 2021

By Primrose Riordan

Financial Times

22 September 2021

Macau casino operators fear end of winning streak with new gaming law

Proposals could force operators to become ‘more Chinese’ as Beijing cracks down on capital outflow.

Bill Hornbuckle, chief executive of casino group MGM Resorts, was confident last week that China’s regulatory crackdown on tech, education and online gaming would not extend to Macau, the world’s biggest gambling centre.

“We’ve gotten zero direct signal that there’s a concern at that level,” he told an investor event in Las Vegas. Even with 20-year casino licences set to expire next year, he exuded assurance, confidently predicting that MGM’s would be extended. “We are believing [our licence] gets extended: time to tell.”

But just one day later, authorities in the Chinese territory unveiled the biggest shock to the sector since the start of the pandemic: a sweeping proposal to increase oversight that could wrest control of the lucrative industry away from foreign shareholders.

The news wiped $20bn off the value of listed gambling operators, which include Sands China, MGM China and Wynn Macau. An index that tracks the industry recorded its worst day on record.

Industry executives and analysts were blindsided by the extent of the proposed restrictions, which could force them to impose deep changes to their business, including appointing government supervisors to enforce official policy from within. Gaming licence renewals were also not guaranteed.

Xi Jinping, China’s president, has launched a wide-ranging campaign in recent months to reshape the economy with an emphasis on “common prosperity”, involving wealth redistribution, a crackdown on vice and improved rights of workers and consumers.

“[The law is] part of the national policy to crack down on gambling activities and Macau is part of China,” Pedro Cortés, a partner at Macau legal firm Rato, Ling, Lei & Cortés, which specialises in gaming law. “It’s going to be a fresh era.”

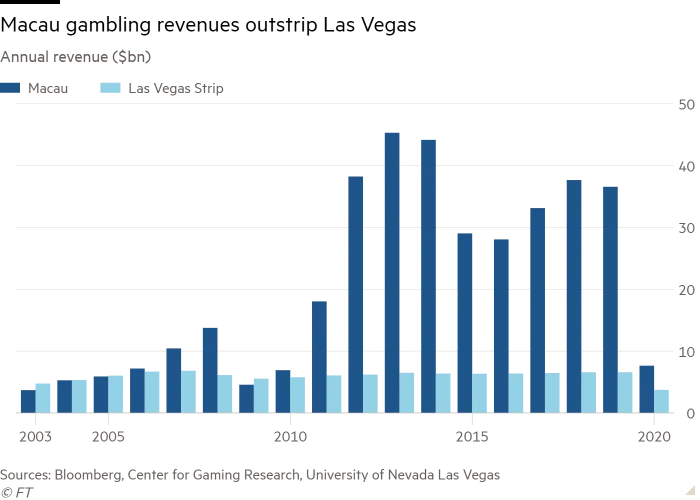

Macau has offered generous tax concessions to its casinos, which earned 292.4bn patacas ($36.6bn) in gaming revenues in 2019, compared with $6.6bn for Las Vegas Strip casinos, according to industry figures.

But the Chinese government has long been unhappy with US shareholders making profits from the territory, believing the economic benefits should stay within the country.

“There is a general perception [that US-listed casinos] don’t leave enough money here,” a former Macau government official said. “China wanted Macau to find a way to not let the money fly out of Macau.”

Casino operators met Macau government officials on Monday, their only scheduled meeting during a 45-day consultation period on the legislation.

The meeting was called so abruptly that descendants of the late casino mogul Stanley Ho, including his daughters Pansy and Daisy who have taken over his holdings, and his son Lawrence, head of Melco Resorts in Macau, were unable to rush back to the Chinese territory in time.

US-listed Las Vegas Sands, founded by the late Sheldon Adelson, MGM and Wynn operate nine resorts in Macau, and their local subsidiaries are listed in Hong Kong. Local operators Galaxy Entertainment, Stanley Ho’s SJM Holdings and Melco, which is dual-listed in the US and Hong Kong, also hold concessions.

All six gaming groups have made handsome returns in Macau, weathering Xi’s anti-corruption drive in 2012 and the coronavirus crisis. The industry’s earnings have started to lift this year after revenues plunged 79 per cent to $7.53bn in 2020.

Underlining the importance of the territory to gaming companies, Las Vegas Sands sold its Nevada properties in March, relying on Macau and Singapore for growth. “Asia remains the backbone of this company,” Rob Goldstein, chair and chief executive of Las Vegas Sands, said at the time.

Sands China, MGM China and Wynn Macau did not respond to requests for comment.

The consultation on the draft law will seek public opinions on how many casino licences, known as “concessions” or “sub-concessions”, should be renewed. It also proposed giving the government a say in whether operators pay out shareholder dividends.

A senior Macau casino executive told the Financial Times that Beijing believed US-listed casinos were “reallocating” their profits back to their parent companies. They added that the government would not fully block dividends in the future, but “if you go overboard . . . that’s a different story”.

“The majority of us thought it was much tougher than expected, especially the dividend,” a second senior Macau casino executive said. “It’s all Chinese money that is being played in Macau. In essence, a lot was going back to shareholders in the US. So knowing China, they would want to keep a greater proportion of the money in Macau.”

The executive added that if the law passed as proposed, US casinos may have to make changes to how they are structured. “The American company can be a shareholder, but [they will become] more Chinese companies,” the person said.

Many of Macau’s casino operators work with local partners; MGM Resorts, for example, has a joint venture with Pansy Ho. This year, Snow Lake Capital, a Chinese investment management company, urged MGM to sell 20 per cent of its China operation to a local “strategic investor”, a move that an industry insider described as an indication of the pressure on foreign gaming companies to localise their operations.

The proposed law would also compel casinos to increase the percentage of share capital held by Macau permanent residents. The move is in line with the local government’s focus on maximising the economic value of its biggest industry, such as through employment guarantees.

Under local regulations, local Macau general managers already hold 10 per cent stakes, but this can be a separate class of non-voting shares, which means they can be held in name only.

Another important part of Macau’s gaming industry that has come under greater scrutiny is promotions known as VIP “junkets”, a subsector that lures and extends credit to high rollers and has long drawn disquiet in Beijing.

The new law “will end VIP gaming and will restrict capital movements”, the former Macau official said. While casino operators were coy at Monday’s consultation, junket representatives were more critical of the proposed legislation, which would criminalise common industry practices.

Yet many casino operators have new properties in the pipeline. The Sands’ Londoner casino and resort, a $2bn redevelopment of its Cotai Central property with a facade resembling the Palace of Westminster and a full-sized replica of Big Ben, is in the process of opening.

More recently, Macau has pressured casinos to pursue non-gaming investments. Melco has invested in a non-gaming resort in Zhongshan, a city across the border in Guangdong province, while Galaxy has a plot in nearby Hengqin.

Alidad Tash, a former casino executive now at gaming consultancy 2nt8 Limited, said the law could signify greater independence for the Macau casino offshoots from their US parents in the future.

“It seems as though [the Chinese government is] not comfortable that three of the Big Six are American. They have to become far more Chinese.” If operators continue to behave as they did in the past, they are “crazy not to be worried”, he added.

_edited.png)

Comments